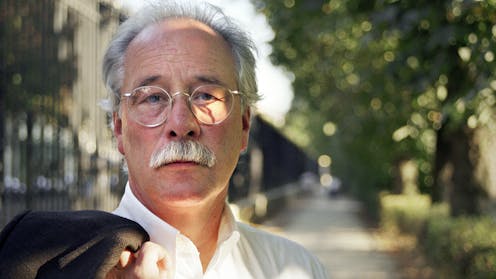

W.G. Sebald’s early critical essays mine his great literary themes – exile, trauma, memory and war

- Written by Linda Daley, Associate Professor in Literary Studies, RMIT University

“Author as well as professor,” was how Winfried Georg (“Max”) Sebald styled himself in the note attached to an article he contributed to a 1990 issue of the experimental Austrian journal, Trans-Garde. Sebald had long harboured a desire to be an author and had a clear plan for becoming one. It included both teaching literature and producing scholarship.

Reading his critical essays, Silent Catastrophes, Essays in Austrian Literature, compiled from Sebald’s two earlier volumes Die Beschreibung des Unglücks (1985) and Unheimliche Heimat (1991), it is possible to see how in the context of his academic career this famed author could be described in Roland Barthes’s terms as a scholar of readerly classical works who became an author of writerly experimental texts.

Review: Silent Catastrophes, Essays in Austrian Literature – W.G. Sebald (Hamish Hamilton)

Perhaps more so, reading these newly translated essays amid (at least) two current wars, it is hard to ignore the currency of this author-professor’s early critical works as explorations of what history may fail to register.

For Sebald, the past seeks its form in literary expression by aiming to articulate the trauma of its destructiveness and the melancholy of lost homelands.

Sebald’s view of history is calamitous and influenced by Walter Benjamin’s “angel of history” as described in his final essay, Theses on the Philosophy of History. Sebald admired the angel as a figure for thinking about the past. He viewed the past as Benjamin viewed the angel: hurtling with its back toward the future and seeing only the wreckage at its feet.

Sebald was born in 1944 in the Alpine region of Germany. This region had experienced none of the visible destruction from Allied bombing of major German cities in the latter war years. His father fought in the second world war as part of the Wehrmacht. Imprisoned until 1947 and, consistent with the widespread postwar German silence, he never spoke of his own experiences to his son.

From a certain vantage, it might have seemed that war and its devastation had never happened. Sebald was particularly angry at this silence among writers (with the few exceptions he acknowledges), a silence later described by the psychoanalysts, Alexander and Margarete Mitscherlich, as West Germany’s collective “inability to mourn”.

Sebald termed this inability a “silent catastrophe”. He later came to speak that silence through his literary inventions, which appeared in the final decade or so of his life: Vertigo (1990), The Emigrants (1992), Rings of Saturn (1995), and Austerlitz (2001).

These titles show Sebald as the great, unclassifiable author he became. Not quite a novelist, memoirist or historian yet somehow all three – with his unique mode of hybridised expression. In a few short years, he went from being a secret reading tip for connoisseurs to shortlisted for the Nobel Prize.

A proving ground

Before these career-defining literary works, the questions Sebald posed for his writing were those of a literary scholar: how might this silence be made legible through analyses of the psychological and social structures depicted in 19th and early 20th century Germanophone literature? What was the relation between life and literature in language cultures other than German that were affected by Germanic authoritarianism and fascism?

Silent Catastrophes contains 19 critical essays relating to 17 Austrian fiction writers (and one poet) responding to these questions.

Sebald wrote most of his essays and fiction works in German even though he lived and taught in England for more than 30 years, overseeing the translation into English of all his books. Having arrived in England in 1966 for his MA at Manchester University, he began his career at the University of East Anglia in 1970, became professor of European Literature in 1988, and remained there until his death in a car accident in 2001 at the age of 57.

Translator of this present volume of works, Jo Catling, was a close colleague of Sebald from 1993. She rightly states in her introduction that Sebald’s “fiction”, not his criticism, marked the pinnacle of his career. And yet it is Sebald’s criticism that she has spent more than a decade of her own career translating for an Anglophone audience.

Like fellow Sebald scholars, Uwe Schütte, Richie Robertson and Ben Hutchinson, Catling views Sebald’s critical writing as a kind of proving ground for the creative expression of his ideas about exile, trauma, memory and history in his later works.

Why Austria?

But why Austrian literature for this German-born scholar and author?

Significantly, for Sebald, Austrian literature was not German literature. Its status was peripheral to the canon of Germanistik, the standard approach to the study of German literature and criticism spanning authors from Goethe to Thomas Mann. Undergirding Germanistik was the belief that literature is the expression of transcendent values, unaffected by history.

For Sebald, postwar Germanistik was worse than ahistorical. It reinforced the “conspiracy of silence” about fascism’s legacies and contributed to the “smug” silence surrounding the postwar “miracle” of economic reconstruction. According to Schütte, the Germanistik Sebald rejected was a politically compromised academic discipline tainted by its involvement with Nazis.